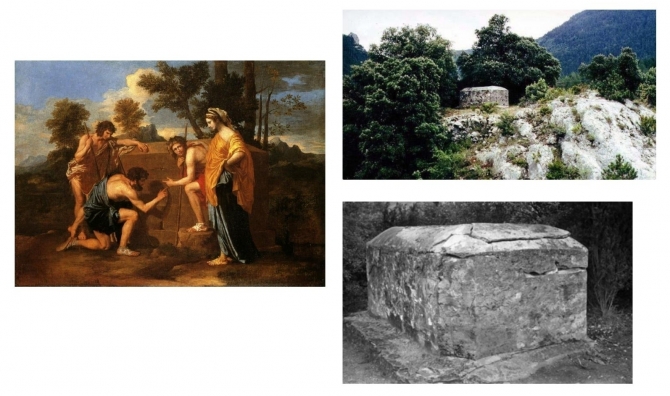

“Et in Arcadia ego” is the inscription that appears, in encoded form, on the funerary slab of Marie de Négri d’Ables, Marquise of Blanchefort. It is also one of the most renowned inscriptions in Western art history, having been employed in several significant seventeenth-century paintings and sculptures—most notably by Nicolas Poussin, as the epitaph in his celebrated painting Les Bergers d’Arcadie (1638–1640), which will be the focus of the present analysis.

The phrase Et in Arcadia ego may be translated literally as “I too am in Arcadia”, where Et stands for etiam (“also”), while the verb sum (“I am”) or eram (“I was”) is implicitly understood.

Beyond its surface meaning, the inscription lends itself to multiple layers of interpretation and is capable of generating remarkably coherent anagrams, among which the most striking are:

ET IN ARCADIA EGO → I TEGO ARCANA DEI

(“I conceal / I guard the secrets of God”)

ET IN ARCADIA EGO SUM → TANGO ARCAM DE IESU

(“I touch the tomb of Jesus the God”)

An analysis of Poussin’s painting reveals the presence of extremely precise geographical references which, due to their verifiability, cannot reasonably be dismissed as coincidental. The mountainous profiles depicted in the background correspond unmistakably to well-known elevations in the Razès region, in close proximity to Rennes-le-Château—namely Mont Cardou, Mount Bugarach, Mount Blanchefort, and the hill of Rennes-le-Château itself.

This landscape exactly matches the view observable—when seen from a specific vantage point—near a now-vanished sepulchral structure once located in the same area, historically known as the Tombeau des Pontils, whose history we shall now briefly outline.

The so-called Tombeau des Pontils, which could still be seen until recent years before its demolition by the landowner, was a tomb remarkably similar to the one depicted in Poussin’s painting. Well known throughout Languedoc and later beyond, it derived its name from the locality in which it stood, Les Pontils.

Crucially, the Tombeau des Pontils does not predate Poussin’s work. Rather, it was erected in 1930, following the geometric and structural canon of the parallelepiped tomb portrayed in Les Bergers d’Arcadie, and built upon the foundations of an earlier tomb dating to 1903. This detail is of particular importance, as the site occupies a location that constitutes a crossroads of astonishingly coherent geographical and geometric correspondences.

The tomb, so strikingly reminiscent of Poussin’s painted sepulcher, became widely known through the work of Gérard de Sède, who discussed it in La Race Fabuleuse – Extra-Terrestres et Mythologie Mérovingienne.

Notably, the Tombeau des Pontils is aligned—within a remarkably small margin of error for the period, approximately 200 meters—beneath the Paris Meridian, which runs from the North Pole to the South Pole and passes through the center of the Paris Observatory, located at 2° 20′ 13.82″ east of Greenwich.

To many researchers, this alignment constitutes an explicit and intentional signature: a selective signal addressed to a knowledgeable recipient. It suggests the intervention of an individual—or a restricted circle—possessing advanced and highly specialized knowledge, who intended to discreetly reveal the significance of that location only to those capable of recognizing and understanding such markers.

One of the most apparently paradoxical aspects of this narrative lies in the fact that Nicolas Poussin never visited the Razès region during his lifetime. While initially perplexing, this circumstance finds a plausible explanation in the figure of Ambroise Frédeau, a close friend of Poussin and a noted local painter who worked extensively in the region near Toulouse. Frédeau frequented a workshop located between Limoux and Alet, where the landscapes of the Razès were commonly depicted as backgrounds. It is therefore entirely plausible that Frédeau assisted Poussin by providing accurate visual references when the latter wished to portray that specific terrain.

Given the influence wielded by clergy at the time—and particularly by Henri Boudet, author of La Vraie Langue Celtique—as well as the modest size of the region and its population, it is reasonable to hypothesize that Boudet, still alive at the time, could easily have identified the owners of the land in question, namely the Galibert family, and persuaded them to erect the Tombeau des Pontils at that precise location. The construction itself was carried out by Bourrel, a mason from Rennes-les-Bains.

It is significant that this occurred in 1903, precisely during the period in which Bérenger Saunière was transforming the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene and its surroundings with the symbolic and allegorical elements examined throughout this study.