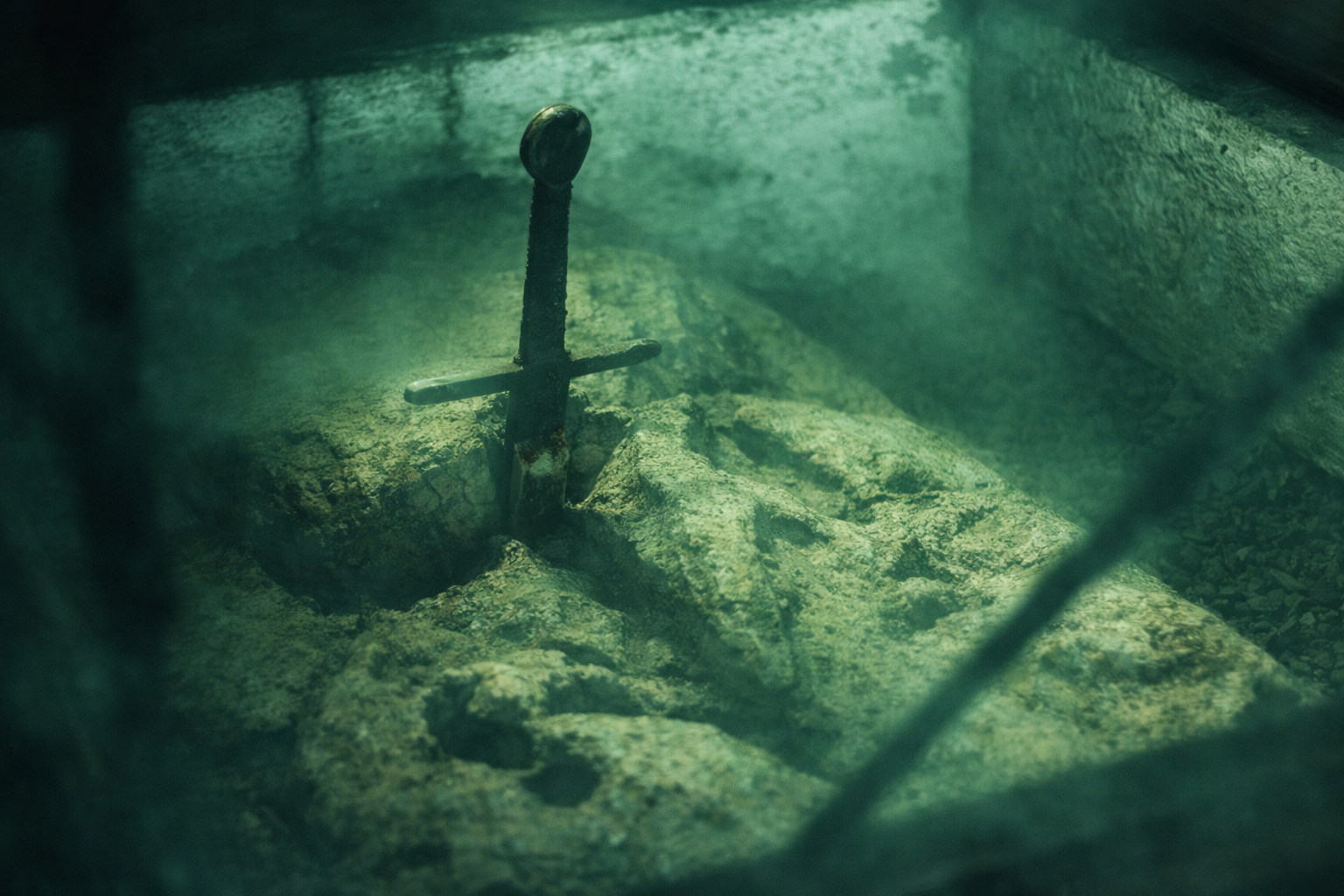

In Tuscany, within a 14th-century chapel at San Galgano, alongside frescoes attributed to Ambrogio Lorenzetti, a striking relic is preserved behind armored glass: the skeletal remains of arms and hands traditionally believed to have belonged to one of the unworthy who attempted to extract the Sword of Saint Galgano from the rock.

According to legend, these individuals failed in their attempt and were punished for their presumption. What transforms this legend into a subject of serious historical inquiry, however, are the chemical and forensic analyses conducted by Luigi Garlaschelli and Maurizio Calì, which indicate that the bones may indeed date back to the 12th century.

This chronological convergence opens a compelling field of connections linking Saint Galgano, the Arthurian cycle, and the symbolism of the Round Table.

San Galgano and the Arthurian World

Several scholars have noted a series of converging indications suggesting a relationship—symbolic, cultural, or narrative—between Saint Galgano and King Arthur.

The first is linguistic: the name Galgano bears a striking resemblance to Galvano (Gawain), one of the most prominent Knights of the Round Table. Beyond onomastics, there exists a dense network of historical connections between Tuscany, particularly the Val di Merse, and medieval France.

This region was traversed by the Via Francigena, the great pilgrimage route that connected Italy to northern Europe. Through this corridor, stories, symbols, and traditions circulated between Tuscany and the France of Chrétien de Troyes, the seminal author of the Arthurian romances.

William of Malavalle and the Transmission of the Legend

According to certain historical interpretations, the transmission of the Galgano narrative into the cultural milieu of Chrétien de Troyes may have occurred through William of Malavalle, another hermit figure associated with Tuscany.

Some scholars go further, proposing that William of Malavalle may not only have been of French origin but could even have belonged to the royal lineage of Aquitaine. If so, this would offer a credible channel through which the Tuscan legend of the Sword in the Stone reached the heart of medieval French literature.

From this perspective, the original formulation of the Sword in the Stone would have emerged in Tuscany in the late 12th century—despite the traditional Arthurian chronology placing King Arthur several centuries earlier.

The Sword in the Stone as Initiatic Symbol

Beyond questions of historical precedence, the allegory of the Sword in the Stone remains one of the most powerful symbols in Western initiatic tradition.

Every symbol and every allegory must be approached as a prism with infinite facets, capable of revealing multiple truths that are not necessarily reducible to a single interpretation. No solitary reading is sufficient to “close the circle.”

In this specific case, the Sword in the Stone can be read as the image of our most intimate, authentic, and profound nature, striving to emerge into consciousness. To bring it to the surface, one must contend with one’s own rationality.

Reason, refined over time as a necessary instrument, can—under certain inner thresholds—become a quagmire of mental, cultural, and psychological conditioning. In such moments, rational coherence ceases to protect and guide; instead, it confines, limiting inner horizons and obstructing truly radical transformations, even when the inner means and justification exist to achieve them.

This conflict—between ingrained automatism and the fluidity of evolving awareness and pure intuition—is perfectly represented by the Sword pressing against the resistance of the Stone, striving to emerge despite the friction.

Between History and Initiation

Whether approached as historical convergence, symbolic transmission, or initiatic allegory, the case of San Galgano occupies a unique position in the landscape of Western tradition.

Here, legend, archaeology, and symbolism converge—not to offer definitive answers, but to invite disciplined inquiry, contemplative attention, and a deeper understanding of the perennial language through which tradition speaks.