Antoine Bigou, chaplain to the noble Blanchefort family, was the first custodian of the celebrated parchments, which he himself prepared, together with the documents belonging to the Marquise.

In 1732, Marie de Négri d’Ables, Marquise of Blanchefort and wife of François d’Hautpoul, became the depositary of an important—possibly decisive—family secret. Along with this responsibility, she was entrusted with a set of documents intimately connected to that secret. These papers, together with a testament, are believed to have been delivered to a notary in 1644 by François-Pierre d’Hautpoul, and, after his death, to have passed from notary to notary until they ultimately reached the Marquise of Blanchefort.

Her husband reportedly attempted on several occasions to recover these documents or to learn their contents, but without success. The Marquise succeeded in excluding him entirely from the secret. It was at this juncture that she prepared her own testament, entrusting the documents to Antoine Bigou.

Marie de Négri d’Ables died on 17 January 1781, and from that moment onward Antoine Bigou honored his commitment with utmost discretion, precision, and diligence.

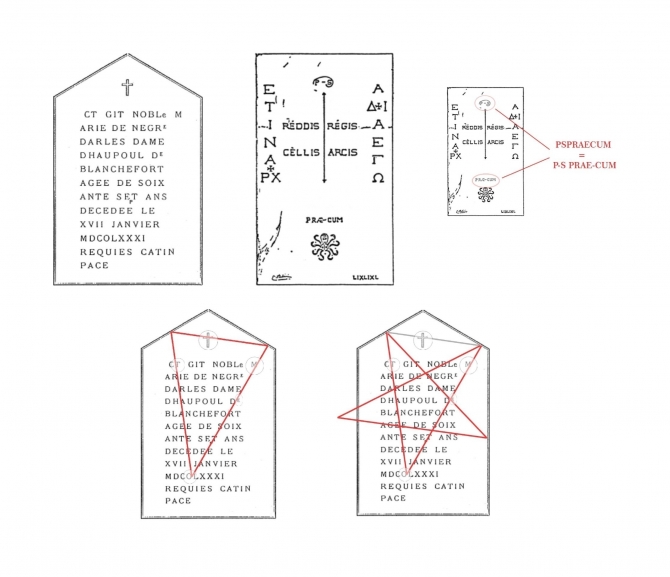

Abbé Bigou is credited with producing both the funerary stele (to the left) and the tomb slab (to the right) of the Marquise of Blanchefort, as well as with creating the famous parchments that contained the crucial knowledge confided to him by the Marquise on her deathbed.

One of the most significant interpretative keys emerges from close examination of the funerary stele. According to the surviving reproductions, the inscription contains a series of apparently deliberate linguistic anomalies which, taken together, reveal a coherent structure. Certain letters are noticeably smaller than the others—specifically: e, E, E, P—while a single M stands isolated. Furthermore, the date of death includes an anomalous “O”, which has no correspondence in Roman numerals. The presence of an R in ARLES instead of the correct ABLES constitutes an error so conspicuous as to appear intentional. Similarly, the substitution of a T for the expected I in the opening line further reinforces the impression of deliberate encoding.

When appropriately reordered, the eight extracted letters form the words “MORT” and “EPEE”—that is, “death” and “sword”, or “death by the sword”. This formulation resonates strikingly with the historical account of the assassination of King Dagobert II, who was killed by a sword thrust during an ambush in a forest near Stenay.

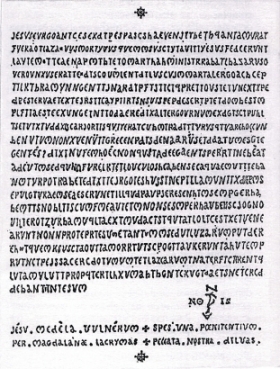

The compound key “MORTEPEE”, when applied via the Vigenère cipher to the so-called Great Parchment, yields a decoded sentence of 128 letters, which will be examined later in this study. This sentence, in turn, provides indications pointing toward specific works of art of particular relevance.

The inscription on the stele itself consists of 119 characters. When combined—errors included—with the 128-character sentence derived from the Great Parchment, the two texts form a perfect secondary cipher of 247 letters. By writing the two texts separately and eliminating all letters common to both, the remaining characters spell precisely “PS PRAECUM”, a phrase that corresponds to an inscription found on the tomb slab itself.

In addition to these textual elements, the stele also contains hidden geometric structures of remarkable precision. By connecting the anomalous letters to the Cross of Christ engraved on the stone, one obtains a perfect isosceles triangle and a pentacle, both constructed in exact accordance with the golden ratio. This provides mathematical and geometrical confirmation of the author’s intent and technical competence.

It must be noted that one line of investigation proposes that the original stele may have been free of linguistic anomalies, and that the version known today was instead reworked by Bérenger Saunière, who may have inserted the encoded elements himself rather than Bigou.

Moreover, the tomb slab of the Marquise contains a particular combination of Greek letters which, when transliterated into Latin, yields a phrase of decisive and startling significance: the celebrated motto found in Nicolas Poussin’s Les Bergers d’Arcadie—a work to which we shall return later.

As for the parchments prepared by Bigou, they were concealed within the church of Rennes-le-Château along with other documents, where they remained hidden until their discovery by Bérenger Saunière. This secret constitutes the very origin of the so-called Affair of Rennes-le-Château.

Abbé Bigou subsequently transmitted the secret to another priest, Abbé Cauneille, who in turn passed it to Father Émile François Cayron and to Jean Vie, parish priest of Rennes-les-Bains and predecessor of Abbé Boudet. This transmission is of particular importance, as Émile François Cayron was the mentor of the young Henri Boudet, later curé of Rennes-les-Bains.

This connection is fundamental, for it establishes a direct link between Antoine Bigou and Henri Boudet, author of La Vraie Langue Celtique et le Cromleck de Rennes-les-Bains—a work widely suspected of being a cipher that may lead directly to the true tomb of Jesus in the region of Languedoc.

Carbon copies of all the documentary materials—among them the celebrated parchments—were produced by Bérenger Saunière himself and later inherited by his devoted housekeeper Marie Denarnaud, his universal heir. In 1938, Denarnaud attempted to locate the grandfather of Pierre Plantard de Saint-Clair, who was already deceased at the time. It was on that occasion that she first came into contact with the young Pierre Plantard, then only eighteen years old.

During one of these meetings, in that same year, Marie Denarnaud entrusted Plantard with several copies of the original carbon copies. From that moment onward, Plantard felt himself invested not only with the material custody of that deposit, but also with the moral and spiritual responsibility that accompanied it.

The documents received by the young Plantard included copies of the two parchments forged by Abbé Antoine Bigou, as well as transcriptions of documents to which Bigou had gained access through the Marquise of Blanchefort-Hautpoul, Marie de Négri d’Ables.

“Pierre et Papier”

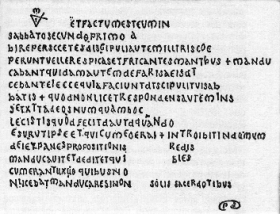

Philippe de Chérisey later authored a forty-four-page document entitled Pierre et Papier, in which he provided certain partial elements of decoding and claimed authorship of the parchments. It can now be stated with confidence that this claim was not truthful and was made for reasons that have since lost their relevance.

This assertion by de Chérisey constitutes the principal reason why many researchers have mistakenly concluded that the parchments were mere fabrications created by him. In reality, the elements presented in Pierre et Papier fall far short of representing a complete decoding key.

A competent cryptological analysis readily demonstrates that the cipher system employed in the parchments is exponentially more sophisticated than the framework proposed by de Chérisey. His contribution represents only a very limited fragment of a far more complex encoding structure underlying the documents.

Among the most significant elements deciphered to date is the coded message contained in the so-called “Small Parchment”, which explicitly links King Dagobert II, later venerated as a saint, to the Order of Sion:

“A DAGOBERT II ROI ET A SION EST CE TRESOR ET IL EST LA MORT”

This may be translated literally as:

“To King Dagobert II and to Sion belongs this treasure, and it is there dead.”

The phrase may also be interpreted as:

“This treasure belongs to King Dagobert II and to Sion, and it lies there, dead.”

Such an interpretation opens the possibility that the “treasure” in question—explicitly associated with both the king and Sion—may in fact be a tomb endowed with sacred significance. This could refer to the burial place of Jesus Christ, or of a crucial descendant in the dynastic lineage, possibly Sigebert IV.

Equally important is the second encoded message of 128 characters, derived from the so-called “Great Parchment” through the application of the Vigenère cipher, using as its decoding key the sequence of letters extracted from the Blanchefort Stele, which yields the word MORTEPEE.

The decoded statement reads:

“BERGÈRE, PAS DE TENTATION, QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF, PAX DCLXXXI, PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU, J’ACHÈVE CE DAÉMON DE GARDIEN À MIDI POMMES BLEUES”

This message was subsequently encoded in visual form by Bérenger Saunière himself during the 1886 restoration of the Church of Rennes-le-Château. He did so by installing the stained-glass window that projects the celebrated “Blue Apples” each year on January 17, and by placing the Demon Asmodeus as a symbolic guardian.

The message refers explicitly to Les Bergers d’Arcadie by Nicolas Poussin, and—based on landscape clues and the phrase “PAS DE TENTATION”—possibly to one or more versions of David Teniers’ paintings Saint Anthony and Saint Paul. According to the logic of the message, these works conceal a decisive key pointing toward a secret of paramount importance which, within the coherence of the overall symbolic framework, appears to indicate the location of a sacred burial site—potentially that of Jesus Christ.

It is particularly noteworthy that the demon Asmodeus is depicted with his gaze directed downward, as if deliberately indicating the presence of something of great importance beneath the church floor. No private individual, association, or institution has ever been granted permission to excavate beneath the church. Nevertheless, based on the structural surveys conducted by Belgian architect Paul Saussez, it is considered highly probable—if not virtually certain—that a crypt exists beneath the pavement.

This hypothesis is further supported by the historical fact that the church functioned as a burial place for local nobility, a circumstance corroborated by parish records and historical chronicles.

The Outer Garden and the “External Church”

In January 1891, Bérenger Saunière obtained municipal authorization from the administration of Rennes-le-Château and commenced the construction of the garden in front of the church, entirely at his own expense.

On June 21 of the same year, the garden was inaugurated, and a statue of the Virgin Mary was placed atop the Carolingian pillar from the old altar, installed in an inverted position. As with previous anomalies, this inversion appears deliberate rather than accidental, reinforcing a consistent symbolic logic.

Further clarifying the function of the outer garden is the placement of the Calvary, which—both in alignment and spatial position—serves as yet another specular double of the altar located inside the church.

The inversion and repositioning of the Carolingian pillar constitute a fundamental element, particularly when considered alongside the numerous other inversions observed within and around the church complex.

One striking example of this intentional symmetry is provided by Saunière’s handling of the “Dalle des Chevaliers”. Discovered face-down before the altar, it was removed from the church and relocated outside, where it was placed face-up at the foot of the Calvary—once again establishing a precise mirror relationship with the high altar inside the church.

A simple plan of the church and garden reveals that the footprint of the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene is reproduced in exact mirror form within its garden, and vice versa.

In this mirrored arrangement:

- the church’s central aisle becomes the path leading to the Calvary,

- the confessional corresponds to the inverted pillar,

- the high altar is reflected by the Calvary itself.

Thus, the exact perimeter of the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene is reproduced specularly in its garden, forming what may be understood as an external church—a deliberate, symbolic inversion that completes the initiatic architecture conceived by Saunière.