The birth of the Templar Order, which Knights were known as Pauperes commilitones Christi templique Salomonis ("Poor companions of arms of Christ and of the temple of Salomon"), better known as Knights Templar or simply Templars, were the best combat units trained and disciplined of their own time, precursors of modern special bodies or elite units, their origin is placed in the Holy Land around 1118-1119 with the aim of ensuring the safety of the many European pilgrims who continued to visit Jerusalem. The order was officially established in 1129, assuming a monastic rule, through Bernard de Clairvaux.

The dual role of monks and warriors, which marked the Templar Order, aroused division within the Christian world.

Over time, the Templar order also devoted itself to commercial, productive, agricultural and financial activities, managing the assets of pilgrims and becoming the most advanced and widespread banking system of the time. Thrived over the centuries in wealth and influence, the Order was targeted by the King of France, Philip IV of France, which culminated, through a process begun in 1307, with the final dissolution in 1312.

The birth of the Templar order is to be placed historically at the center of the wars between Christian and Islamic forces that broke out after the first crusade, called by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1096. At that time the streets of the Holy Land were invaded by marauders and muslim fanatics who attacked and looted pilgrims. In 1099 the Christians recaptured the Holy Land from the hands of the Muslims.

THE DISSOLUTION OF THE TEMPLAR ORDER

Innocent II's bull Omne Datum Optimum dated March 29, 1139, was of vital importance for the Order of the Knights Templar because it sanctioned the total independence of his work and being exempt from paying any kind of tax.

After the fall of St. John of Acre in 1291, three hundred German and French crusader barons landed in Cyprus and lived here as hermit monks. The Order, however, after the definitive loss of the Latin States in the Holy Land, started towards its twilight, the fundamental reason for which it was established ceased to exist. Its dissolution, however, did not take place by ordinary procedure from the Holy Church, but through a series of infamous accusations disputed by the King of France, Philip IV of France, with the intention of eliminating his debts and taking possession of the Templar heritage.

On September 14, 1307 the King sent sealed messages to all the bailiffs, seneschals and soldiers of the Kingdom ordering the arrest of the Templars and the confiscation of their property, which were performed on Friday 13 October 1307. The move succeeded as it was shrewdly initiated in contemporary against all the temples of France; the knights, summoned with the excuse of tax assessments, were all arrested and imprisoned.

The charges against the Order were among the worst possible: heresy, idolatry, sodomy. In particular, they were accused of worshiping a mysterious pagan deity, the Baphomet. In the prisons of the King, those arrested were tortured until they began to confess heresy. On November 22, 1307, Pope Clement V, faced with confessions, ordered the arrest of the Templars throughout Christianity with the Bull Pastoralis Præminentiæ.

On 12 August 1308, the Bull Faciens Misericordiam was promulgated by Pope Clement V in which the accusations brought against the Order of the Temple were defined.

Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Order, who at first confessed the charges, retracted them, being burned at the stake on March 18, 1314 in front of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, on the island of the Seine of the Jews.

In 2000, the Italian scholar and researcher Barbara Frale found a document in the Vatican Archives, known as Chinon parchment, which shows how Pope Clement V intended to forgive the Templars in 1314 by acquitting their Gran Master and the other heads of the order of the charge of heresy, and merely suspend the order rather than suppress it. The document belongs to the first phase of the process, in which the Pontiff still intended to save the order, even if at the cost of subjecting it to a profound reform.

CLOTHING AND UNIFORM

The Templars were identifiable by their white, black, or gray (with a white cloak only for the knight brothers) surcoat, to which was later added a distinct red patent cross, embroidered on the left side.

Among the symbols of the Templars there was the beauceant, characterized precisely by the cross red license in black and white field.

Pope Innocent III, had granted the Order total independence from temporal power, including the exemption from the payment of taxes and gabelles, in addition to the privilege of being accountable only to the Pontiff himself and to the possibility of demanding tithes.

The presence of the Templars on the territory of both continents, Asian and European, was ensured by the various Templar headquarters: the Preceptories and the Fortress Houses, largely autonomous from the point of management view.

In the great capitals (Paris, London, Rome and others) there were the Houses, each of which had control of one of the seven great provinces from England to the Dalmatian coasts where the Templars had divided their monastic organization. At their peak, they presumably arrived at thousands of locations, spread across Europe and the Middle East, indicating their considerable economic and political influence during the Crusades.

From a structural point of view, four types of confreres could be summarized:

- the knights, equipped as heavy cavalry

- the sergeants, equipped as light cavalry, from the humblest social classes of the knights

- the brothers of trade and the factors, who administered and operated in the properties of the Order.

- the chaplains, who were ordained priests and took care of the spiritual needs of the Order.

- Various degrees of command and administration responsibility were attributed to the Grand Master, the Commanders, the Sénéchaux, the Marshals, the Gonfalonniers and other roles.

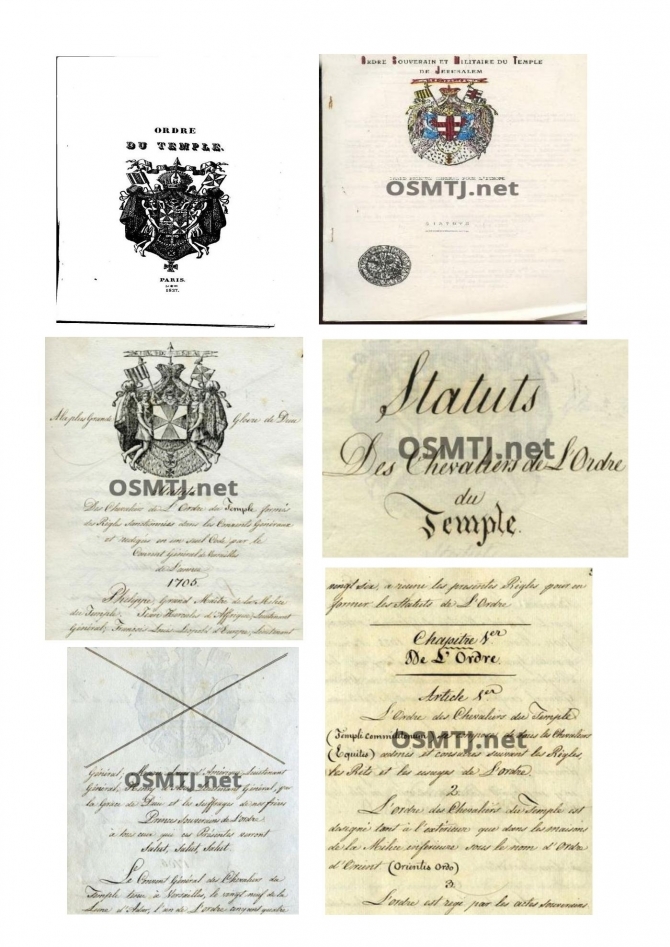

THE RULE

The Knights Templar, assumed a rule of monastic form, only with the Council of Troyes of 1129 blessed by the support of Bernard de Clairvaux, substantially based on some basic elements of the Benedictine Rule.

Of the original Templar Rule there are some written finds, written in Latin, which in that historical period is the official language used in formal, religious and lay texts; later versions favor the ancient French language instead.

The three classic vows of the monastic orders - poverty, chastity and obedience - are not explicitly expressed. The exhortation to chastity appears only in the chapters of the appendix and seems above all to discourage the coexistence between Fratres and Sorores, implicitly admitted however as a previous custom, to be avoided for the future. The consent to the entry of married men and to the possibility of a temporary adhesion to the Order, substantially irreconcilable with a permanent chastity, is evident; at the same time it discourages any kind of intimacy with women, be they relatives, mothers or outside the family. With regard to the vow of poverty, the knights are urged to donate all their assets (only half if married) in favor of the Order, allowing however the possession of land and the enslavement of men and farmers.

In other later texts the practice of war booty is admitted. In relation to the vow of obedience, the intent to preserve a strict collective and coordinated discipline appears clear, with limits especially directed to the ostentation of clothes and accessories, personal decorum, daily rules, prayer, food and collective solidarity. The ban on the practice of acts of superfluous or unnecessary violence, such as hunting, is severe and unequivocal. The successive versions of the rule received to date, are written in French and are much more detailed and full of instructions concerning above all military life, resulting more consistent with the functionality of a highly structured military Order.